The Tech Behind The Magic

Ahead of its delay, a unique, innovative production creates challenges and lots of excitement.

HGO lighting supervisor Michael James Clark remembers, back in March 2020, taking a sad walk around the bayou north of the Wortham Center. He was on his cell phone with the technician and incoming crew for The Magic Flute, and he had to tell them to cancel everything due to COVID-19.

“When it got shut down,” he tells Cues, “the set was in the rehearsal room, the media servers and projectors were on the way to Houston… It was very much within striking distance of getting everything here.”

This blockbuster production had already been making its way around the world, from its start with the theater group 1927 and directors Barrie Kosky (Komische Oper Berlin) and Suzanne Andrade (1927). Clark was eager to try his hand achieving the visual and technical spectacle of it all. When HGO had to cancel, so much preparation had already been done at the Wortham that, to him, it was like “having a long race and getting to that finish line,” but not being able to cross it. Nor did he know if he ever would.

And all the excitement Clark and the HGO creative team had stashed away back at the start of the pandemic is back with electrifying force.

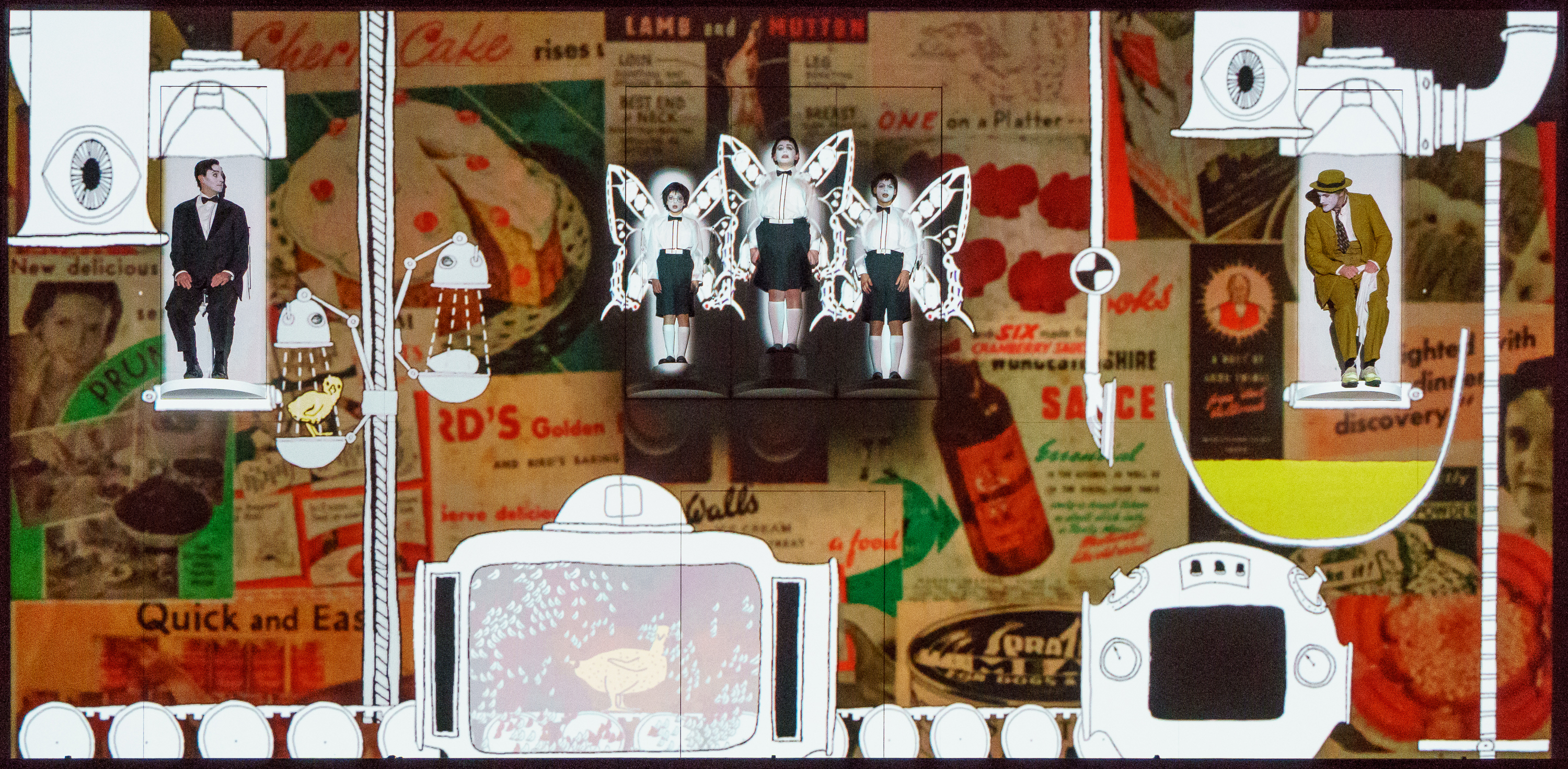

The technology is in place, and the team has been working hard on perfecting its implementation for The Magic Flute’s opening night. With the curtains ready to rise and reveal this production’s unusual set—a white projection screen with doors and rotating platforms that allows artists to interact with silent-film-style images—months of preparation and fine-tuning have been piled on top of all the work put in back in spring 2020.

There’s a lot of moving parts involved in Kosky’s production. The projected images allow little room for error. While they must appear interactive, they can only be manipulated a small amount, which makes this production unlike all others in HGO history. For a normal production, Clark explains, “everywhere it goes it’s going to be fundamentally different,” accounting for differences in place, performer, available space and equipment, and the instant-by-instant chemistry of human artists on stage. With this production, the images often come at the performers relentlessly, requiring unusual precision on their part.

It makes sense, then, that an essential aspect of rehearsals is having the special projection equipment fully implemented and a technician on hand to fine-tune how every single image connects with each character’s movement and music. The technical crew can subtly manipulate a specific image beforehand to account for a performer’s height or gait. Or they can delay its movement ever so slightly.

So much goes into each moment. For example, say a performer lifts her hand to hold a projected bird. Pulling this off requires the crew to have programmed in her preferred timing and the height at which she will hold her hand.

Meanwhile, the artist must act out the moment exactly as she did in rehearsal, in the precise place, at the precise moment, and with the same precise movement. During performances operators can create pauses between projected moments (“padding,” Clark calls it), but with dozens or even hundreds of animated images on the screen-stage at any given time, recovering from missed cues can be difficult.

This version of The Magic Flute presents other unique challenges for performers. The set, constructed to be a surface for projections, is fitted with areas for real people. Artists can occupy various spots behind it, both on the floor and on elevated platforms, which can rotate to position them in just the right place at the perfect moment. Often, a performer will then be stuck there. During her “Queen of the Night” aria, soprano Rainelle Krause must be suspended high above the stage, her limbs restricted as she sings, as fellow soprano Andrea Carroll reacts energetically to projected images on the stage below.

This is all very different from how other productions depict that same scene, often with the Queen chasing her quarry around the stage, allowing the performers to navigate the moment in real time. The demands of the Kosky production mean the actors are held in place by the images, one of them literally bound to a wall.

Such a creative and innovative, but exacting, new way to produce Mozart’s classic opera brings excitement along with challenges. The artists and staff, who’ve had to create a new workflow while solving so many novel problems, have been looking forward to this production for a long time.

"I think a lot of us are really excited to just see this,” Clark says, “and experience what has become such an iconic version of this show, finally, on our stage."