Romantic Encounter: Madame Butterfly at HGO and “Meiji Modern” at the MFAH

Backstage Pass Note: The exhibition Meiji Modern: 50 Years of New Japan, running July 7 to September 16, 2024 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, will shine a fascinating light on Japan during the mid-nineteenth to early-twentieth centuries. Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, running January 26 to February 11, 2024, premiered in 1904 and is set in Japan during the same period. We are delighted that Bradley Bailey, the Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao Curator of Asian Art at the MFAH, has written an essay about Meiji Modern for HGO audiences to enjoy. His essay and accompanying images from the upcoming MFAH exhibition provide wonderful insight into what was happening in Japan at the time when Madame Butterfly was written.

Puccini’s Madame Butterfly was in part inspired the travel memoir Madame Chrysanthème (1887) by Pierre Loti (1850-1923), who visited Nagasaki, Japan in the summer of 1885. Published to great acclaim in 1887, Loti’s semi-fictional travelogue was translated into numerous languages (including Japanese) and even inspired Vincent van Gogh to paint his portrait La Mousmé [image from NGA]. Though his sitter was French, Van Gogh nonetheless gave the painting a Japanese-inspired title: musume is Japanese for young girl, and the painter noted in his letters that he learned this word from Madame Chrysanthème.

Both Puccini’s opera and Loti’s memoir tell the story of a romantic encounter, but they do so almost entirely from the point of view of visitors to Japan. Indeed, during the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries, Western visitors to Japan were often fascinated and even shocked by the beauty, mystery, and eccentricities of the country’s culture. However, what Loti and Puccini leave out is that many Japanese themselves were equally fascinated by these foreign visitors to their shores.

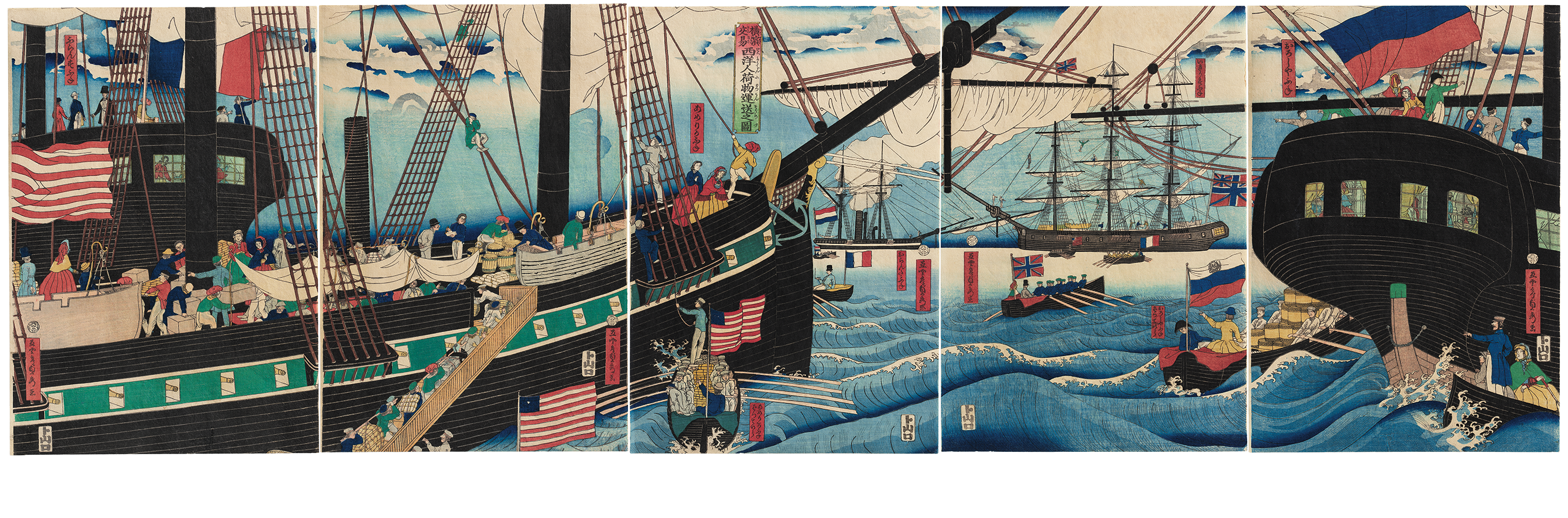

Meiji Modern: 50 Years of New Japan (July 7 - Sept 16, 2024) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells the other side of this encounter between Japan and the outside world, bringing together nearly 200 works of art that showcase the mystery, awe, and inspiration Japanese artists took from these new people, materials, and ideas from abroad. When Commodore Perry arrived in Edo Harbor in 1853, he effectively ended 250 years of near total isolation on the Japanese archipelago. Soon, other foreign ships followed, as demonstrated by a striking print by the Japanese woodblock print designer Utagawa Sadahide (1807 - 1873) [cat 2-20 Picture of Western Traders at Yokohama Transporting Merchandise] made in 1861. Featuring the port of Yokohama, to which foreign trade was initially confined, the artist captures the imposing nature of the large so-called “Black Ships” from abroad, which teem with life. Sadahide places the American ship at the forefront of the design, allowing the citizens of Tokyo—who had never before seen a European but could experience the sight vicariously through this print—to peer onto deck and, in some cases, inside the ships to observe the exotic foreigners and their wares. By overprinting in blue, the artist is able to simulate the glass windows of the ships, an exciting detail as glass production did not exist in Japan at this point. It must be noted, however, that just like Pierre Loti’s ship, the actual ships of Yokohama did not have women aboard. Instead, the artist has copied printed images of foreign women and added them to the scene, making this print even more informative—and thus marketable—to the curious public.

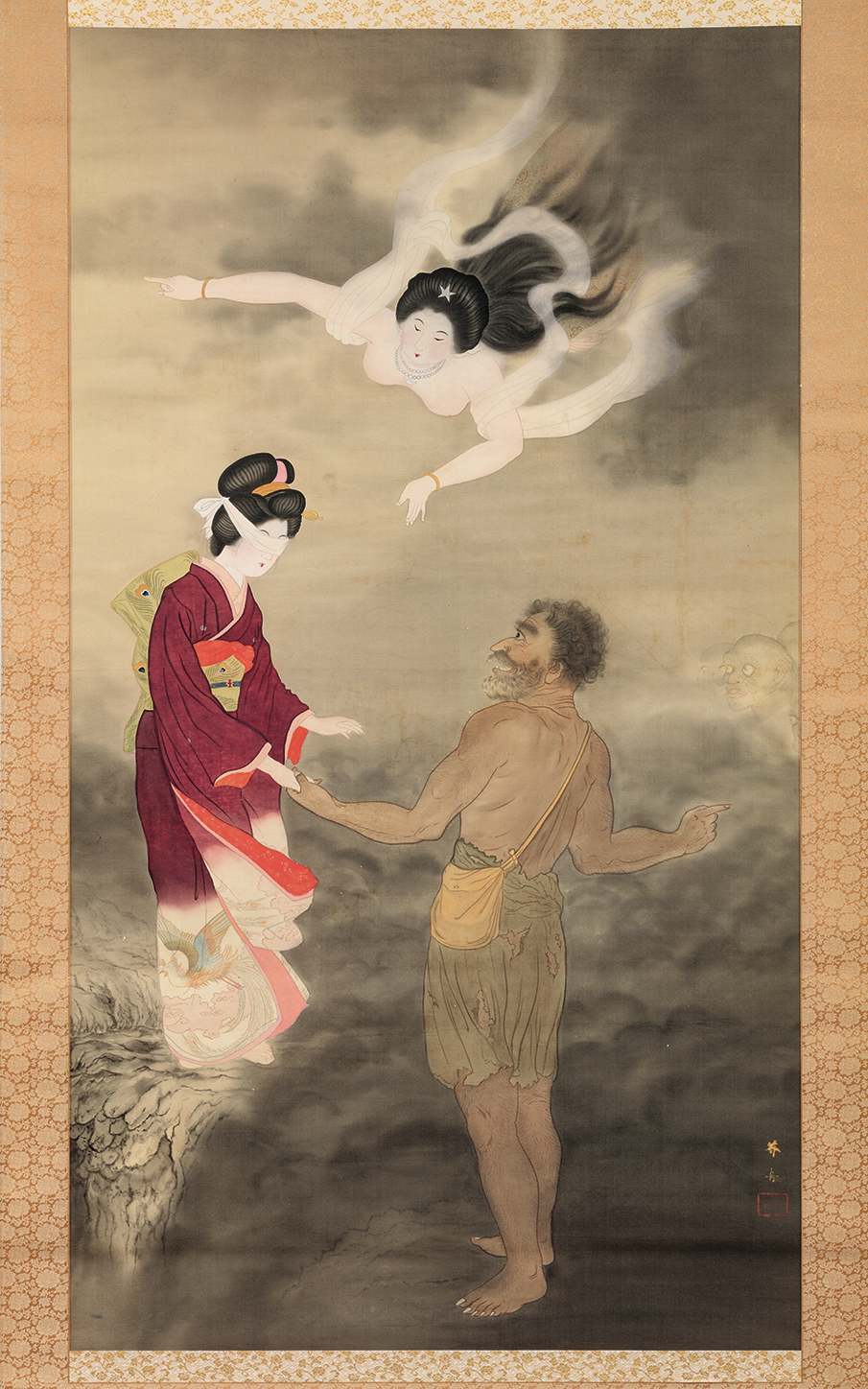

During this period, however, not every Japanese person was enthusiastic about these newly established foreign relations. Indeed, as a newly discovered painting, Temptation (1907) by Kaishū [cat 1-17] reveals, many feared the foreigners would bring ruin upon Japan, as many European empires had done in South and Southeast Asia. This painting features a beautifully dressed Japanese woman, her kimono emblazoned with a phoenix and her obi decorated with peacock feathers, who is blindfolded and standing on the edge of a cliff. At right, an unkempt foreigner—whose non-Japanese ethnicity is emphasized through an enlarged eye, protruding nose, and curly hair—gestures rightward; his mouth is open as if he is attempting to convince her to follow him off the cliff. At rightmost edge of the painting, eerie figures can be seen, reminiscent of the hungry ghosts that populate Buddhist Hell, indicating the foreigner’s sinful intent. At the top of the work, a figure meant to resemble an apsara, a heavenly Buddhist musician, flies in as if to rescue the woman. She gestures left, away from the cliff. Interestingly, on her head she wears a five-pointed star, painted in glittering silver. This is not a reference to Buddhism but instead likely refers to the stars of the Japanese Imperial Navy, which was growing in might during this period; like the apsara, the navy offered protection against foreign incursion. The existence of this painting, a recent discovery from an important Hawaiian collection, indicates that not every Japanese of the period shared the enthusiasm of Puccini and Loti’s female characters.

Unlike the Madames Chrsanthemum and Butterfly, in reality, the women of Meiji Japan experienced unprecedented levels of freedom and social opportunity. Imperial decrees on education for the first time included girls and, as a result, there was a proliferation of women’s schools, finishing schools, and colleges; widespread female literacy; and a thriving economy driven by female spending. For example, Kajita Hanko’s elegant art nouveau postcard, Student, shows one of these modern girls of the period, complete with her red hakama (pants) which were worn atop a kimono, signaling a girl’s enrollment in school.

With increased female literacy came increased demand for female-centered and oriented stories, inspiring a new genre of magazines which published serial stories of romance and longing, specifically targeted toward women. Each issue contained a beautifully printed woodblock which illustrated one of the stories. For example, in one illustration [cat 3-27 Tomioka Eisen frontispiece for White Robed Kannon] a handsome artist is superimposed against a beautiful woman, who has been silhouetted against a bright red artist’s palette. This story recounts the tale of a romance doomed by the debt of a woman’s family and the low pay of her struggling artist beau. Other examples feature more subtle and intimate portraits of femininity, such as two compositions by Mizuno Toshikata [cat 3-29 and cat 3-30] which reflect the newfound cosmopolitanism of Meiji Period women. In one, a woman is shown writing, using an imported European style pen instead of a Japanese brush, while the other takes a more self-referential approach, depicting a woman reading.

Finally, one of the most exciting ways women found to express themselves during this period was through their fashions and hairstyles. In earlier periods, sumptuary laws and caste-like systems strictly dictated self-presentation. By the late-19th century, however, Japanese women had many more options. Toyohara Chikanobu’s composition of “chignons” [cat 3-32] expresses the excitement this new variety of styles brought. This print was actually made to be cut up, akin to a paper doll, allowing the owner to “try on” different hairstyles using the central figure. Each hairstyle is accompanied by instructions as well as an official title. The titles range from the purely descriptive, such as “rolled up” or “half down,” to the more imaginative, like fishtail braid, second from the left, known simply as “The Margaret.”

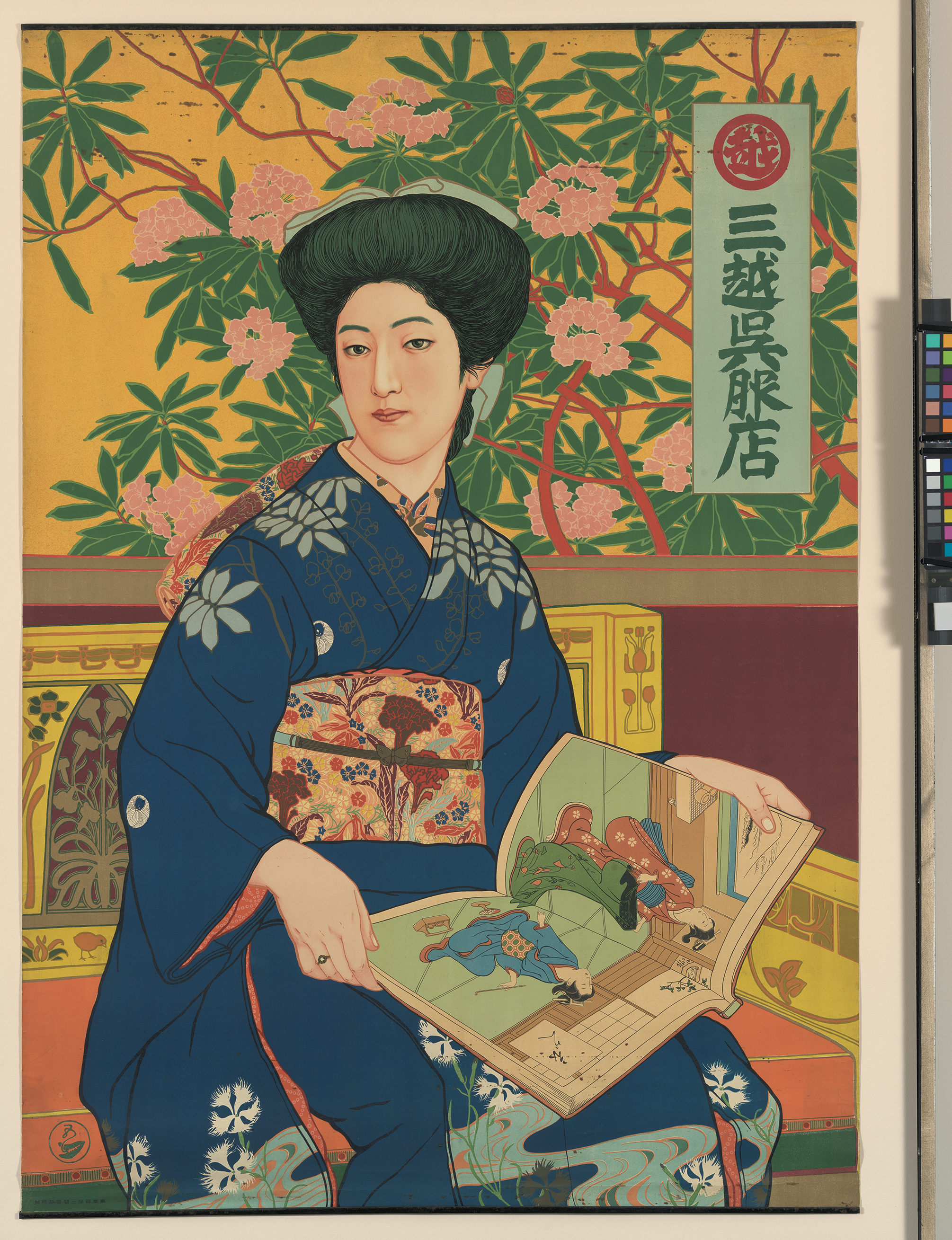

Fashions, especially female fashions, also gave rise to the now world-famous Japanese department stores, many of which still exist today. One final work, a rare lithograph by the great painter and print designer Hashiguchi Goyō (1880-1921), illustrates this beautifully. Made for Mitsukoshi, this design won a major contest for the store and was printed in great numbers, though few originals survive today. Now a major chain of department stores, Mitsukoshi originally dealt in kimono, like the fashionable navy-blue example seen here. Seated atop an art deco bench, the woman also sports a Victorian bouffant hairdo with loosely tied bow and wears a pearl ring, a foreign accessory. This assortment of modern—and foreign—objects expresses this woman’s cosmopolitan sophistication as a truly modern beauty. Goyō heightens this contrast with the inclusion of an 18th century woodblock printed book on her lap, which shows a kimono dressing scene. This nod to the past at once references the long Japanese tradition of printmaking while also emphasizing the fashionable and contemporary beauty of a modern Japanese woman who, unlike the many other female protagonists of many operas and memoirs written by men, gazes outward, directly and confidently, into the eyes of her beholder.