Life on the Other Side

We come from a place up north

Where they say all your wishes come true

But we had just one wish this time of year

To come to spend Christmas with you.— Translation, “Navidad en México,”

El Milagro del Recuerdo

El Milagro del Recuerdo captures an intimate snapshot of the family lives of two men, Laurentino and Chucho, as they make a surprise visit home to Michoacán, Mexico from the United States on Christmas Eve, 1962. The pair arrive in Santa and elf costumes, carrying novel gifts, customs, and expectations from America, alongside their worn boots and hats.

Laurentino and Chucho are braceros who have been away on contract in Texas. At the Christmas celebration, their families must grapple with new ideas, lost time, and the difficulty of maintaining close bonds through long periods of separation. It is a timeless narrative that still reverberates today. The joy, excitement, and tension are palpable.

So, what does history tell us about the experience of real-life braceros—laborers working in the U.S. as part of the Bracero Visa Program? Records and interviews with former braceros tell us that it varied quite a bit and depended on many factors, chief among them the humanity, or lack thereof, of those who employed them. And though experiences were different for each bracero, it was not an easy life for most.

The Bracero Visa Program, which existed from 1942 to 1964, started as a common-sense solution to American labor shortages during World War II. Diplomatic agreements between Mexico and the U.S. allowed Mexican citizens to receive short-term visas to work in American industries suffering from wartime labor shortages. Industries spanned railroad maintenance to farming, and contracts were available in many states across the country, with Texas and California being the largest employers.

At its outset, the program offered benefits for both parties. American industries received critical labor support, and Mexican workers received legitimate employment with the promise of an American wage. However, the program grew more and more complicated as laborers fell victim to government negligence and employer greed.

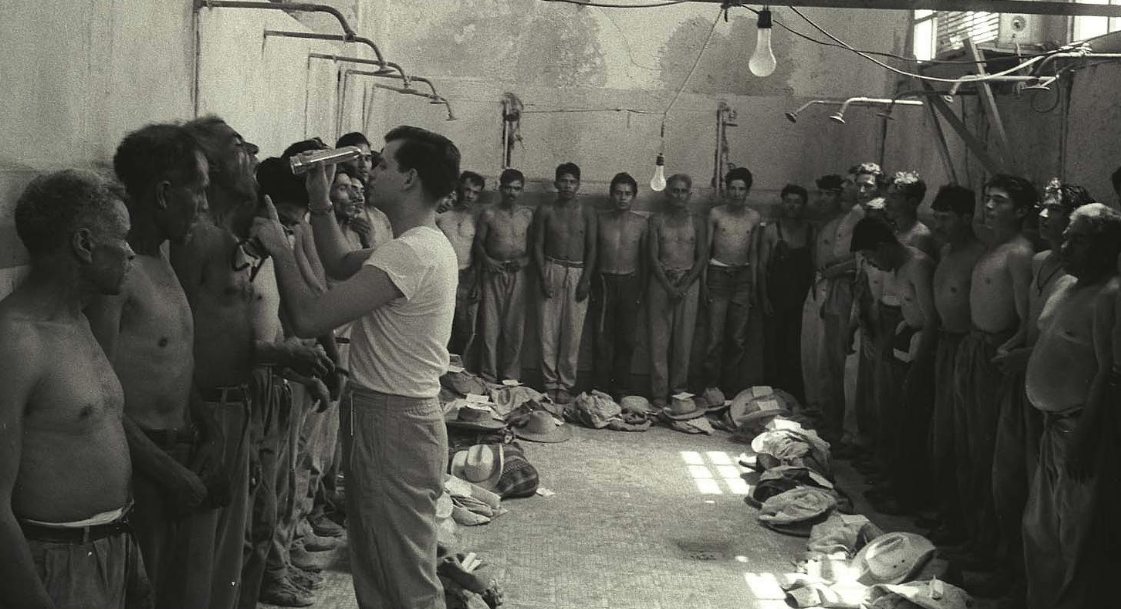

A bracero aspirante (hopeful candidate) began his journey at a Reception Center, where his fitness for the program would be judged by physicians and employers. Reception Centers were located in the U.S., especially in Texas and California, and served as a first entry-point for newly arrived Mexican workers. In these centers, aspirantes were subjected to invasive physical examinations and fumigation before chosen candidates were dispersed to their region of hire.

With only their Alien Laborer’s Identification Card and whatever possessions they could carry on their backs, the selected workers were loaded into transportation vehicles for dispatch. Some ex-braceros later reported extortion by reception officers who extracted an unsanctioned “processing fee” in exchange for program inclusion. Others recalled feeling inhuman during the examination, like cattle undergoing inspection. Rio Vista Farm Reception Center, one of the last remaining centers in existence, is located in Socorro, Texas and is currently undergoing restoration and transformation into a museum.

Braceros lived in barracks-style accommodations typically situated on or nearby their place of work. Some barracks were originally intended as housing; others were converted from chicken coops or stables and outfitted with stretched-canvas mattresses and a single wooden shelf for possessions. Although contracts stipulated employers provide safe, sanitary housing and food for braceros outside of their wages, greedy employers collected fees for these necessities, and supplied substandard provisions in return. Charges were filed against contractors for violations such as feeding braceros sub-grade meat and housing hundreds of men in a single building.

Workdays were long and laborious. Having no transport of their own, workers were beholden to their employers to drive them to and from worksites each day. To cut costs, some vehicles were fashioned from cattle cars refitted with wooden benches to carry men and their equipment between sites. Cramped and unsafe, these vehicles contributed to a number of underreported injuries and deaths. Once braceros arrived at the jobsite, they began a day of backbreaking labor.

Despite harsh conditions, the promise of a prevailing American wage to send home to their families kept braceros coming back for new contracts. The exact wage a bracero was paid depended on which region or industry he worked in, and whether he received payment based on hours worked or amount produced. Regardless of region or payment style, braceros in every part of the country received far less than their American counterparts.

Texas agriculture employers were notorious for underpaying their braceros if they paid them at all. Poor program oversight and legal representation allowed many employers to withhold or neglect wages, even though braceros were bona fide workers in the eyes of the American government. Later attempts to petition the American and Mexican governments for lost wages after the program’s termination were futile, as neither government took responsibility for laborers’ exploitation.

Although many ex-braceros vividly recalled their hardship within the program, they also acknowledged the excitement of bridging their new life in America with the one waiting for them in Mexico. Generous contractors were known to drive their braceros into town on the weekends to shop, meet people, and experience the city. Many men enjoyed the opportunity to experience contemporary American life beyond the gaze of their families.

Some braceros were married with wives and children in Mexico, but many other young, single men used these outings to meet significant others. Men who married American women often chose to stay and raise their family in the U.S. Some married men with families in Mexico saw a new life for themselves in America and resettled with wives and children. These blended families would go on to forge an amalgamation of cultures that continues to shape many of the traditions practiced in both countries today.

However, the influence of American culture on these men was not always viewed positively in traditional Mexican communities. At a time when many Mexican families lived in poverty, durable work clothes and electronic gadgets stood out as extravagant. Seasoned braceros typically enjoyed the luxuries of a radio, denim jeans, and work boots, while newer recruits toiled in the fields in linen pants and leather sandals. Adopting laid-back attitudes, materialism, and a modernized perspective on women, wealth, and leisure left many braceros ostracized when they returned home.

In addition to the tension between their Mexican and American lifestyles, laborers in the segregated South also experienced rampant racism. Southern Americans, operating with a Jim Crow mindset and Cold War era xenophobia, ousted braceros from Whites-only restaurants, bars, and shopping centers with signs reading “No Blacks, Dogs, Mexicans.”

Notably, braceros were also treated coldly by some Mexican Americans, who denigrated them as neither American citizens nor full assimilates. As World War II ended and job competition mounted, braceros won labor contracts over their Chicano peers because they unwittingly broke strikes and accepted lower wages. To supplement the post-war demand for cheap labor, employers began to bypass the program altogether and employ illegal Mexican immigrants, which further fueled existing anti-bracero prejudice.

In the 1950s, with immigration numbers soaring, the U.S. launched a large-scale federal deportation effort, attempting to reverse the massive migration generated by the program. The effort was unsuccessful in displacing hundreds of thousands of Mexican families making their new homes abroad. Therefore, much of the rich cultural diversity in America, and especially in Texas, can be traced to the program.

For so many men, the Bracero Visa Program’s promises of fair wages and working conditions went unfulfilled. In more than a few instances, the opportunity to pursue the American Dream through the program cost men their lives. But for other braceros, the program supported their families and hometowns in Mexico or brought about new lives in America.

One wonders if this audience would be gathered here at the Wortham Theater Center in Houston, Texas, experiencing a mariachi opera, if not for the program and its complicated legacy.