From Page to Stage

Bring your family to see Mo Willems’s Bite-Sized Operas: Slopera! and Don’t Let the Pigeon Sing Up Late! at Miller Outdoor Theatre at 11a.m. on October 8-9, and 6:30p.m. on October 10. For information, call 713-225-0457 or email OperaToGo@HGO.org.

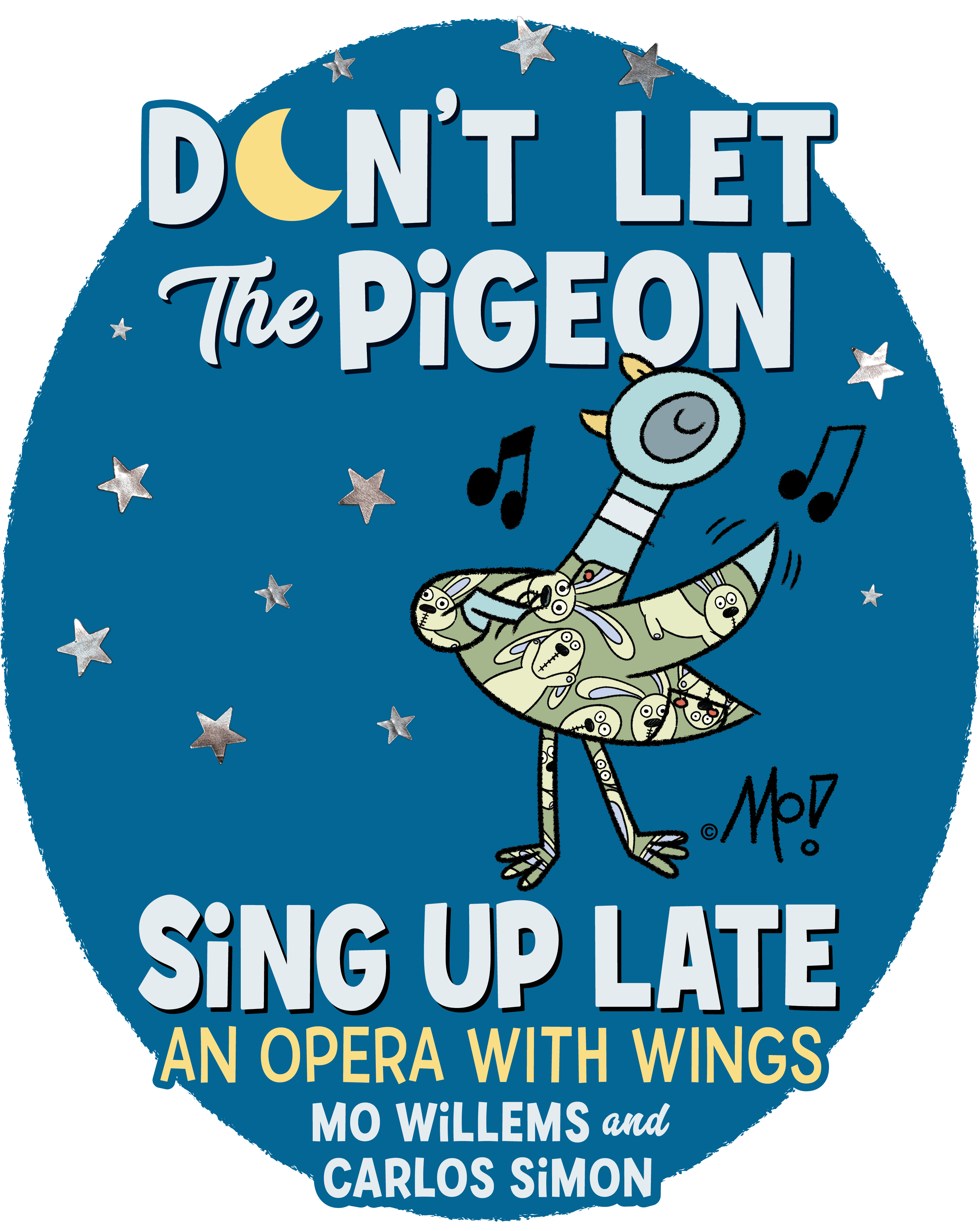

If you have a young child, you likely already know Mo Willems’s hugely popular books. Now, your family has the opportunity to experience two of them in an entirely new way—as an operatic double feature! This season, HGO’s Opera to Go! touring production for students and families, Mo Willems’s Bite-Sized Operas: Slopera! and Don’t Let the Pigeon Sing Up Late!, will be presented at schools, public libraries, and other community spaces across the region.

Willems is a New York Times-bestselling author, as well as an illustrator, animator, and playwright with six Emmy Awards under his belt for his work on Sesame Street. He collaborated with Grammy Award-winning composer and pal, Carlos Simon, to adapt two of his stories into their operatic stage versions that debuted in 2021 at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C., where Willems served as Education Artist-in-Residence and Simon was Composer-in-Residence.

Slopera! sees the friendship between two of Willems’s iconic characters, Elephant & Piggie, put to the test over their different tastes in food, while Don’t Let the Pigeon Sing Up Late! features The Pigeon facing his greatest foe yet: Bedtime. These shows, Willems’s first foray into opera, have been a hit with kids and “former kids” alike. Here in Houston, they will be presented as a bilingual English and Spanish rendition.

The secret to Willems’s success? Treating his audience, no matter their age, with respect. “I try to remember that children share the same DNA as us,” Willems said. “Kids are human beings just like the rest of us. I want to respect their intelligence."

Read on to hear more from Willems about this exciting, family-friendly double feature.

For audiences who may be unfamiliar with Elephant & Piggie and The Pigeon—how would you describe these characters?

Elephant and Piggie are two best friends who fight and making up, like all friends do. And The Pigeon is a bird who, like most people, is unable to differentiate what he wants from what he needs.

Do any of these stories come from a personal place?

So, I am the child of immigrants. I grew up eating my ethnic food when I was a kid. I’m Dutch, so the ethnic food was chocolate sandwiches. I remember people teasing me for it—they called it “bird poop sandwiches” and all this stuff. I couldn’t believe it, because I was eating chocolate, right? I thought that would be cool. Nobody else got chocolate for lunch. But I was teased because it was different. So, I think a lot of the Slopera! original story is, like, How can you not like this? And the fact that Gerald—the elephant—ends up not liking it is fine. Gerald doesn’t try food to do the right thing, necessarily. Gerald is trying to repair a friendship after saying, “No, that’s gross,” and not giving it a fair shot, right? So as a kid, I didn’t want people to want my chocolate sandwiches. I just didn’t want them to hate them without trying it. It’s just what one should do. It’s pure, What would you do in this situation? What would you do when you’re confronted with something new? They’re good questions to ask.

What about these stories do you think lends them to the opera treatment?

The reason to do opera is multifold. One, I knew nothing about it, so that was exciting. I like things that I know nothing about because I can learn from them. The other is that opera and picture books have a lot in common. They only work when they’re performed. You have to say them out loud, unlike a novel, which is quiet. They’re about very big emotions and are very dramatic. Characters have deep, deep, deep feelings. When I discovered that you could make shorter operas, it really excited me, because I know how to write 22 minutes’ worth of material. I’ve been writing television for 30 years, but I didn’t know how to make opera.

What about going from the written word to the world of opera interested you?

It’s exciting to play with things that happen in books. For instance, with early readers, you only have a certain vocabulary that you can use, so you create a rhythm and a cadence. Well, opera isn’t just about rhyming. It’s about cadence, right? And so being able to discover a cadence that works, tells the story, expresses big emotions, and is both funny and serious at the same time was very exciting. And you know what? Kids don’t know what opera is, which is great. They’re just going to come into it and be like, yeah, this is cool. But to have a death scene with Slopera!—and to be able to be that dramatic and be that big—is really cool.

What was the process of turning these books into an opera?

So, it was very collaborative. I worked with Carlos Simon, who’s a great composer. And to the same degree that I did not know opera, he did not know kids. So we were both trying to figure out how to use our vocabulary and our strengths to be able to communicate something. We also had a dramaturg, Megan Alrutz, who I’ve been working with for 16 years. You sort of hope that there’s enough in the story—which is short—to be able to fill it out. You think, What do we need to have? What is in the visual vocabulary? What are the beats that happen in an opera? What are the beats that happen in this book, and where do they overlap? One of the great things about a shorter opera is you can do all the things that happen in a big opera, quickly. That speed also creates a little bit of tension, a little bit of humor.

What about the collaborative process did you enjoy?

I’ve written a bunch of musicals based on my books, so I’ve worked with composers before. I’ve got a basic sense of what I need to do. Fortunately, I had seen some of Carlos’s shorter operas, so I’d heard his music before and was a fan. We were able to discuss what excited us during this process. A scene works best when you can’t really remember who came up with it. When it’s so back and forth, it just sort of grows organically. Both Carlos and I feel very strongly that the story is more important than our egos, so it wasn’t hard for us to throw away things that didn’t work or add things that did. I would write something, and he would say, Yeah, that doesn’t work, I’m just going to write something. I would say, Oh, that’s great, but what if we do that? It was just sort of building things up and tearing them down over and over again, until it felt right.

How did the way you approached the pieces evolve over time?

Carlos and I worked on Slopera! first, and by the time we got to the Pigeon piece, we had a shared vocabulary. We knew how to communicate with each other. He would say, Well, I really want a scene that does this because, musically, I want to get to this point. Or, I feel like the story is asking this question. I want to be able to orchestrate it in this way. I was able to say, Look, I really want a lush sequence, or I want a scary sequence, or I want this. It became just two pals hanging out, playing around, with every now and then, their dramaturg reminding them that, Hey, you’ve got to make sure it’s 20 minutes, got to make sure it’s performable—and the more technical and creative limitations that we wanted to play with.

How does it feel to have your first show with HGO?

I am very excited. I’m super-happy that it’s going to be traveling and that so many kids are going to get to see it. I love the idea that it is bilingual now. Well, trilingual, right? It’s English, Spanish, and the language of music. I think that’s awesome. I love the idea of introducing big ideas and big emotions and new art forms to as many kids as possible, so this is a really great opportunity.

Now that you’ve been bitten by the opera bug, are there any plans on the horizon for future operatic endeavors?

Yes, Carlos and I are very much hoping to do a full-scale opera. We’ve been working on some ideas, putting some stuff together and talking with different organizations. It would be great to really make a big production.

What do you hope audiences take away from this experience?

I hope that they enjoy themselves. I hope even more that when they leave, they start singing, and they start turning their lives into operas, and they start performing. You know, if you’re a kid and you’re frustrated by something, rather than just losing your temper or being sad, to be able to sing about how sad you are is a great way to communicate, right? So, in anything that I do, I’m hoping for two opposite things—one is for people to be impressed by how amazing I am (laughs) and, two, to think, I could do that. I could draw a story. I could write a book. I could sing an opera. When I have big feelings, I can express them through music. That’s my hope.