Clowning Around

Joan Font is an absolute clown. And we use that word with the utmost respect. The 75-year-old Spanish director, who stages this season’s production of Rossini’s Cinderella, is a master in the ancient art of physical humor.

Font was born in Olesa de Montserrat, nestled in the foothills northwest of Barcelona. The village is famous for its elaborate Passion Play—a Holy Week tradition that has been performed since at least 1538. Font’s participation in these pageants as a boy inspired a deep love for theater, which he later pursued as a student in Barcelona and Paris. In France he trained under Jacques Lecoq, a legendary French thespian who specialized in mime, masks, and clowning.

When Font returned to his homeland in the early 1970s, Spain was in the last years of Franco’s dictatorship. The fascist regime had long suppressed Font’s native language of Catalan by restricting literature and instruction. Often mistakenly described as a dialect of Spanish, Catalan is a separate Romance language, primarily spoken in the Catalonia and Valencia regions.

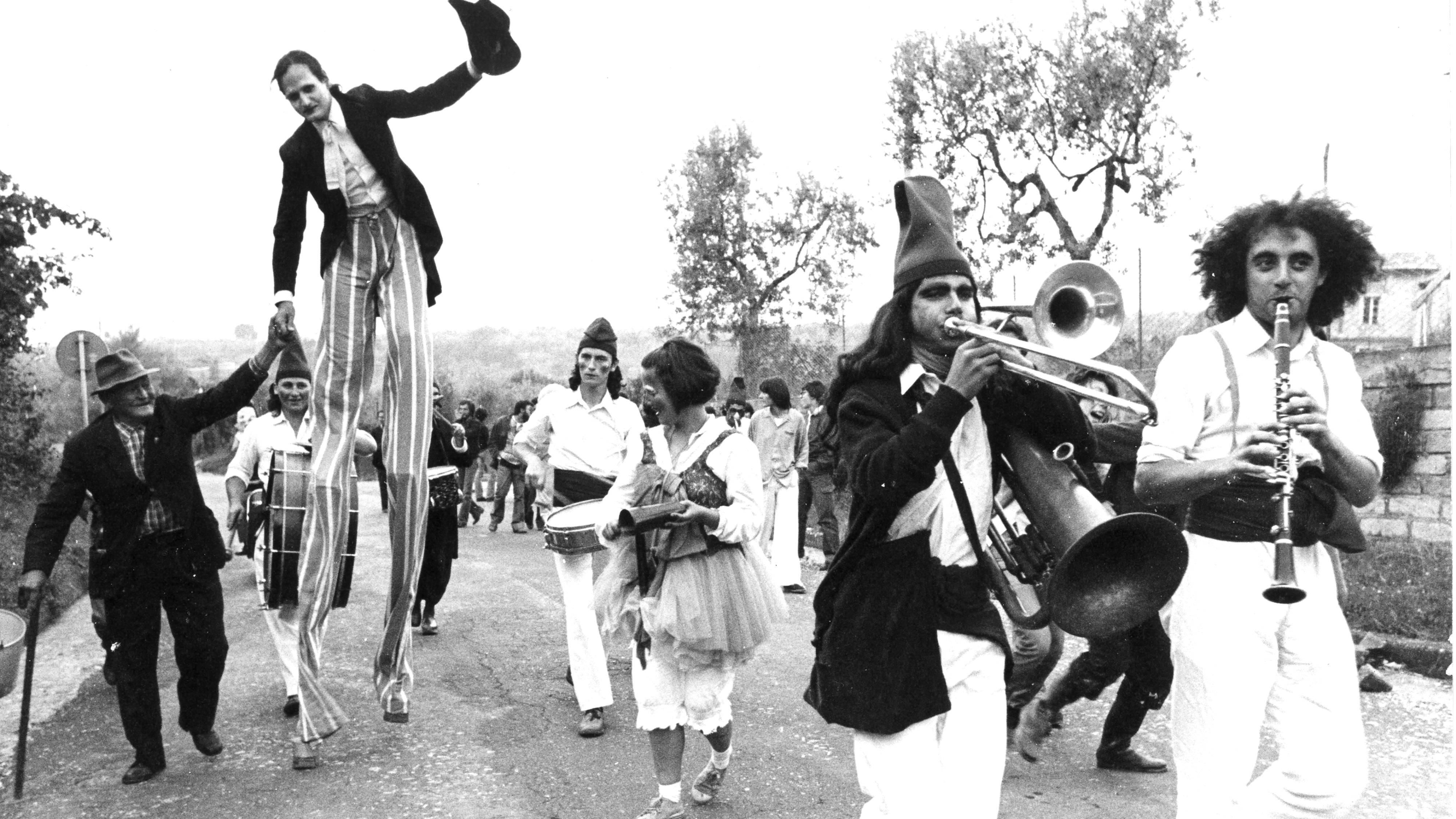

Inspired by the fight for Catalan autonomy, Font and a group of like-minded Barcelona actors took to the streets—on stilts and in red noses. Their resistance naturally assumed a theatrical form. But this was a theater of liberation that broke free of the auditorium, spilling out into the open air to mingle with everyday people. Officially banding together in 1972, they founded an artistic collective called Comediants—Catalan for “Comedians.”

Far from political demonstrations, Comediants’s performances are brimming with a spirit of mischief and whimsy. Their unclassifiable “theater of the senses” combines elements of circus, puppetry, pantomime, carnival, and commedia dell’arte. Enormous glowing balloons drift through the air. A ragtag marching band accompanies jugglers and prancing acrobats. Masked demons dance beneath streams of flying sparks. A pair of clowns clink out a duet on a set of glass bottles filled with colorful liquids. All the world’s a stage for Comediants—whether on a plaza, in a park, or on a pond, they conjure fantastic universes of endless possibility.

True to the troupe’s Catalan roots, Comediants look to local customs for inspiration. Their shows frequently incorporate the eccentric papier-mâché costumes worn during Barcelona’s Feast of Corpus Christi processions. Capgrossos (big heads) are oversized masks that fit overtop the wearer’s noggin and shoulders. Gegants (giants) are massive effigies—some over ten feet tall—that completely cover one’s body, with only their feet sticking out from the bottom. Such traditions, which date to the Middle Ages, are part of what Font terms cultura popular—less “pop culture” than “folk culture.”

In 1999, Font was approached by Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu to direct a production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. It was an opportunity to invade the realm of High Art with Comediants’s revelries—to bring the party indoors, so to speak. “The aim was to transport this cultura popular to the world of opera,” Font tells Opera Cues. “We took all these elements from the street—the elements of a fiesta—and put them on a stage.”

The comic operas of Rossini, which are filled with absurd situations and cartoonish characters, were well suited to Font’s directorial style. In 2007, he staged the composer’s Cinderella at Houston Grand Opera. This was followed by HGO productions of The Barber of Seville in 2011 and The Italian Girl in Algiers the year after.

Cinderella, with its fairytale source, taps into something deep. His work with Comediants, so steeped in folkloric influences, has always been about returning to the mythical, pagan, and ritualistic origins of theater—the primoradial archetypes that connect us as human beings. “Cinderella is a universal myth of all cultures and all time periods,” says Font. “All people have this image of transforming, of emerging from the darkness—from the blackness, the weight, the pain.”

The theme of transformation is at the core of Font’s production. “Nothing is as it appears,” he explains. “And our point of view is on this line between reality and dream.” In his staging, the doorway emerges as a powerful symbol. This magic portal, which Font likens to Lewis Carroll’s looking glass, represents the gateway to the imaginary—the threshold where we cross into make-believe.

Indeed, the characters always seem engaged in an elaborate game of dress-up: Alidoro disguises himself as a beggar, Dandini and Don Ramiro swap identities, Cinderella trades her rags for a ballgown. Font compares all this masquerading to another tradition of street theater: “It’s like carnaval. You can change your life for one day. Because you’re dressed in a way, you will be treated in different ways. But it isn’t reality.”

It’s crucial for Font that his productions be understood by all. Many of his projects with Comediants transcend language entirely, relying on the kind of physical storytelling the director studied as a young man in Paris. In this sense, he found a kindred spirit in Xevi Dorca, a choreographer and fellow Catalan Spaniard. Dorca’s performances blend clowning and dance, depicting hilariously bizarre sketches. Font enlisted the dancer to devise a language of movement for Cinderella that could be “read” as clearly as a text.

“At the beginning, I had the responsibility of making the rats’ movements,” says Dorca. With their pointy snouts, Cinderella’s silent rodent companions (who don’t figure in Rossini’s original opera) are indebted to the masked mimes of Comediants. “I had to work a little bit on what gestures could represent this animal. And it just came very naturally—going to the floor and finding a few movements that they could repeat.” As a demonstration, he lifts his bent-wristed hands to mimic paws and turns his head sharply to the side.

“Day by day,” Dorca continues, “I’d be working in more detail with the chorus and principals, giving gestures to the characters so that they’re better defined. And I’m always using the music for this. Rossini is very clever. The music explains the story. Even the words are not necessary. You could just listen to the music, and you could understand a little bit of what was going on. And I really use the music—the accents, the atmosphere—to build the different characters. When they go down the stairs, when they walk, when they take a prop, when they move furniture—it’s always connected to the music.”

“The real choreographer here is Rossini,” admits Dorca. He goes on to recount a moment in rehearsal when he proposed adding some dance steps to the ensemble number “Questo è un nodo avviluppato.” It’s a “freeze-frame” moment when each of the characters expresses their shock, one-by-one, in a kind of tongue-twister. “But Joan said, ‘No choreography,’” recalls Dorca. “So I said to him, ‘Let’s do some gestures.’ And I created a sequence that was very, very simple.” He demonstrates an adorable bit of fingerplay, recognizable from “The Itsy-Bitsy Spider.” “It develops with the structure of the score,” explains Dorca. “The audience can see the characters singing more clearly.”

After performances of Cinderella, Dorca is always delighted to spot young operagoers trying out the “Questo è un nodo” hand motion or doing their best impression of what he calls the “rat attitude.” “The child can focus on different aspects of the opera that an adult isn’t going to focus on,” he says. “And Comediants also have these popular performances that are very watchable for different ages and different social levels.”

“We want all the audience to participate as if they were breathing together,” Dorca adds. “All the audience: children, old people, young people, different races, different cultures, religions. We want to give some pleasure and joy—laughing, screaming, whatever they feel!”

“You can tell stories in a way that’s not literal, but emotional,” Font chimes in. “And that was the beginning of Comediants.”