An American Story

There’s a memorably ironic moment in Great Scott, composer Jake Heggie’s 2015 opera with librettist Terrence McNally. Fictional, deceased Italian composer Vittorio Bazzetti, a hybrid of Bellini and Donizetti, is brought back to life during an intermission panic attack suffered by the title character, Arden Scott, who is riskily starring in Bazzetti’s long-forgotten masterpiece. She mentions that she is an American opera singer, and that she is shortly to premiere a new American opera.

“American opera?” Bazzetti sings, “I didn’t know there was such a thing!” Indeed, to nearly any 19th-century person, the words opera and America would rarely have appeared in the same sentence.

From its beginnings as a remnant of the Florentine and Venetian empires of the 17th century until the onset of World War I, opera indeed was a largely European art, even when imported to America. The early Metropolitan Opera seasons, beginning in the 1880s, would not have been out of place in any European capital, and the company maintained that image for a long time. San Francisco Opera was started by the Italian immigrant Gaetano Merola, and for most of its first half-century was very Eurocentric, employing its first American-born leadership only in the 21st century. Chicago was known as La Scala-west for decades.

Not Houston Grand Opera, which was enterprising from the start, opening in 1955 (the same year as Lyric Opera of Chicago) with two operas that were only 50 years old at that time, Madame Butterfly and Salome, starring largely American artists. Subsequent seasons in those early years saw a fair amount of American repertoire, as well.

From the early 1970s onward, this entrepreneurial mantle was expanded and taken on a huge joy ride by General Director David Gockley, from reconstructing the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess and delivering it to its rightful place on operatic stages for the first time since it was written for Broadway, to the largest and most diverse range of American repertoire of any opera house anywhere. This is an American vision of an art born in Europe that continued after David’s departure and lives on today in the company’s new general director and CEO, Khori Dastoor. Replenishing the repertoire with works of our own time is the finest way to honor the legacy repertoire of the past.

Like the fictional Bazzetti, it sometimes surprises people to learn that anyone is still writing operas at all in the 21st century. It seems like such an old-world activity, doesn’t it? Well, they are, and American composer Jake Heggie has led a renaissance in American opera for the last quarter-century. There have been many game-changing operas this century in a huge array of styles, but Jake has been the unbidden leader of this new movement of audience-embracing works, from his first opera, Dead Man Walking, which opened in October 2000 at San Francisco Opera. Before Dead Man Walking opened, David Gockley had determined that HGO should commission his next two full-length operas (how many companies have the vision to commission an opera from a composer before the first has opened!?). They were The End of the Affair, based on Graham Greene’s novel, followed by part one of the retirement of Frederica von Stade, who starred in Jake's popular opera Three Decembers.

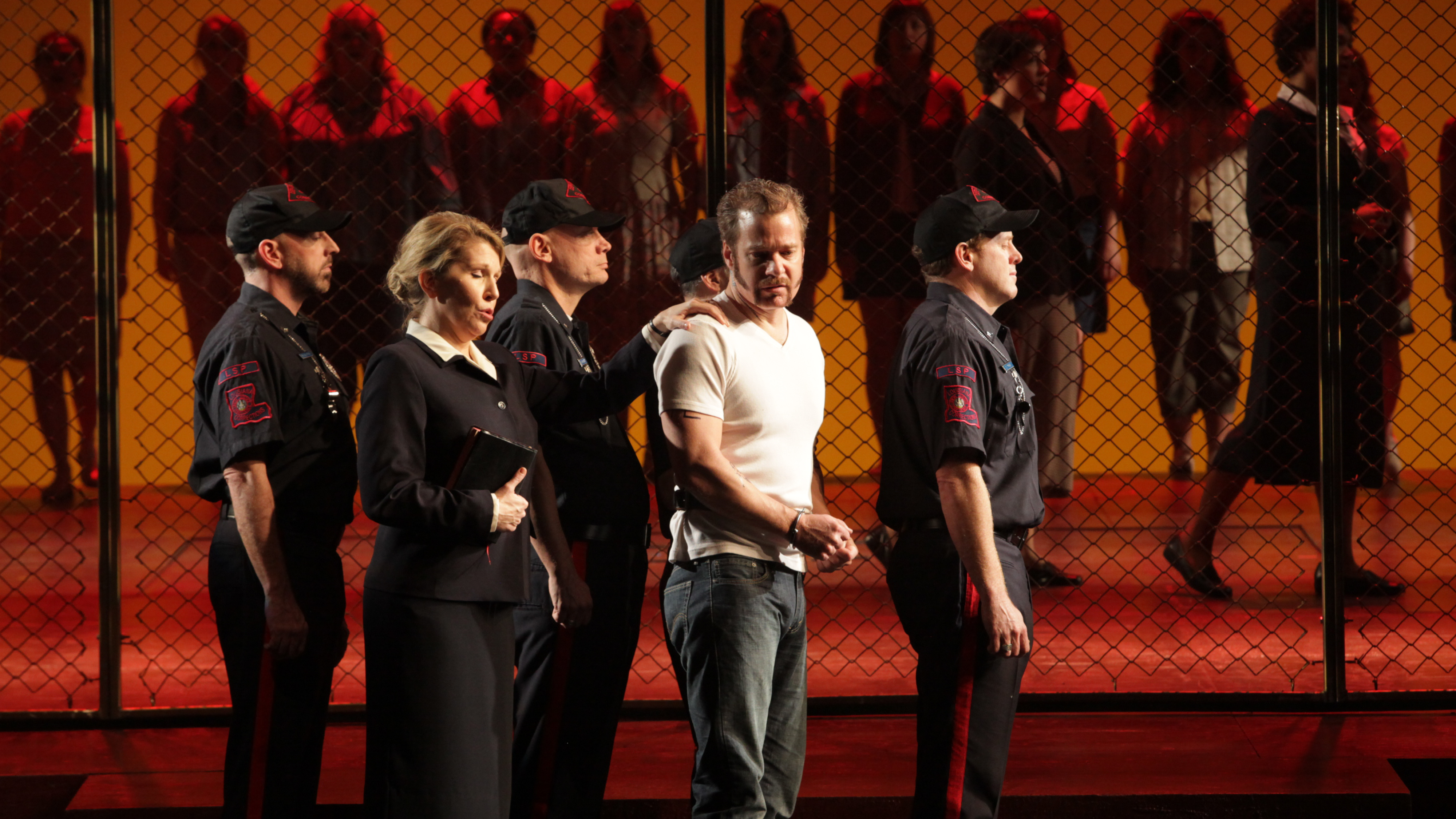

Our northern colleagues at The Dallas Opera commissioned Jake’s next two full-length operas, Moby-Dick and Great Scott, after which he returned to Houston for his 6th large-scale commission, It’s a Wonderful Life, based on Frank Capra’s iconic film, and now this new commission from HGO, Intelligence. This means, obviously, that six of Jake’s seven major operas have been commissioned in Texas, which is a rare and precious bit of operatic history, something of which the state should be very proud.

Jake’s career has been capacious, rigorous, and incredibly broad. He has also been prolific, writing several smaller-scale operas and more than 300 songs to a huge array of poets, many of which are staples of recitals. One of our unforgettable pandemic projects at HGO was his song cycle Songs for Murdered Sisters, with poems by Margaret Atwood, conceived by Butler Studio alum Joshua Hopkins as a memorial to his late sister.

As Jake approached his sixties, a lot of impulses coalesced in him: musical, political, theatrical, social, philosophical. These aren’t musings that surface in daily conversation, but they pull on an artist, like birds knowing precisely when to migrate. Those impulses created the world into which Intelligence emerged, and it is a work that could only have come from a mature artist.

Pablo Picasso was once asked to autograph a napkin for a fan and while doing so, drew a small figure on it, giving the person a very-valuable Picasso sketch in the process. The fan commented with amazement on how quickly he had been able to produce something so valuable. Picasso responded with, “on the contrary; it has taken me my whole life.”

Intelligence is an opera that has taken a lifetime of rich and culminating experience to conceive and compose. Though it is certainly not Jake's final opera, it does represent an epiphanic turning point for him, as did Moby-Dick—nothing he wrote after it was the same as what came before. His extraordinary theatrical imagination places him, at age 62, as the inheritor of the late Carlisle Floyd’s unofficial but deserved mantle as the Dean of the American Opera, a moniker Jake’s own natural modesty would probably refuse.

Intelligence, an opera about the inherited truths of only one life, also aligns with several long-overdue cultural moments of racial reckoning in the United States, a movement that itself sits within complex societal realities about race in this country. No one opera, indeed, no single work of art of any kind, is ever going to do anything but chip away at the immensity and importance of this subject.

Intelligence will have a few detractors who will never see it, because these are the times in which we live. But as a summit of the mature part of Jake’s career, Intelligence is unquestionably the opera he was destined to write at this time (it was first conceived eight years ago), just as surely as he was destined to write his first opera, Dead Man Walking, a quarter-century ago. We turned to him for a new opera because of the totality of his career and his status as an American composer, not because of any single subject.

Any successful writer or composer will be handed countless ideas by well-meaning admirers, and those ideas are always welcome and flattering, even when they are mostly terrible. But when a subject like this one burrows its way into the heart of a creator, nothing can stop it. The story was told to him by a docent at the Smithsonian Institution, and I knew the moment he told me about it that nothing would deter him from it. We should all desire those works that are burning within the greatest creative minds, whether or not they are conventional.

The subject of Intelligence is complex and multi-layered, as it is not “about” any single thing. The ultimate subject of all of Jake’s major operas has been, in various ways, identity: “Who am I,” in the face of an adversary? This took the form of a spiritual journey between two people in Dead Man Walking: Sister Helen Prejean finds herself amidst an unexpected juggernaut of death penalty politics in the American South, but the death penalty is not the opera’s subject. Sister Helen wants only one thing: that the murderer, Joseph de Rocher, accept responsibility for his crime, so that she can ease the pain of his soul, and the opera is about her journey to get him there.

Intelligence tells an American Civil War story, partly fictional and yet real at its most important points. Still, neither the Civil War nor slavery are the opera’s ultimate subject. Like all of Jake’s other operas, Intelligence is deeply about identity, but identity within the world of slavery, civil war, and the gathering of intelligence to win that war. Traumatic family secrets are a deeper part of the Intelligence story. It is an opera about where the truth of our lives can be found, and how corrosive deception always is.

The aim of the opera is beneath its surface, where it tells a single American story of two very real American women, abolitionist Elizabeth and the enslaved Mary Jane, whose lives were intertwined in an era in which families were regularly ripped apart. This single story is magnified millions of times by untold and lost tales within the American diaspora. We all live, at some level, with the generational wounds of our country’s history. There is no escaping them without inflicting untenable amounts of future pain, so we must let our stories be told, however they are told. One story will open doors for future stories, as we have seen countless times.

Intelligence is a rich generational story, a deep call from America’s most renowned opera composer for unity, empathy, and the ignition of important conversations. It marks, also, the operatic debut of director/choreographer Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and her company, Urban Bush Women, whose role in co-creating and theatricalizing Gene Scheer’s dense and rigorous libretto cannot be overstated. `

Intelligence is a landmark in the history of HGO, the first American opera to open one of our seasons, and itself not only a new pinnacle of a composer’s already-illustrious career, but the launch of a new era of the company’s role in what is now a thoroughly American art: opera. Yes, Maestro Bazzetti from Great Scott, American opera is alive and thriving in a place you would never have heard of: Houston, Texas.